“To name the soils that you come from is to acknowledge that you were not self-made, because there is no such thing as a self-made human. It places you in the context of an ecosystem. It confesses that you are a creature—simply, someone created by forces beyond you—which is to say reared and scarred and sanded and formed. It admits that you are not some nebula floating in the ether but that you have roots and are inescapably interdependent with the world around you.” (Good Soil, 24-25)

There’s great risk in reevaluating vocation.

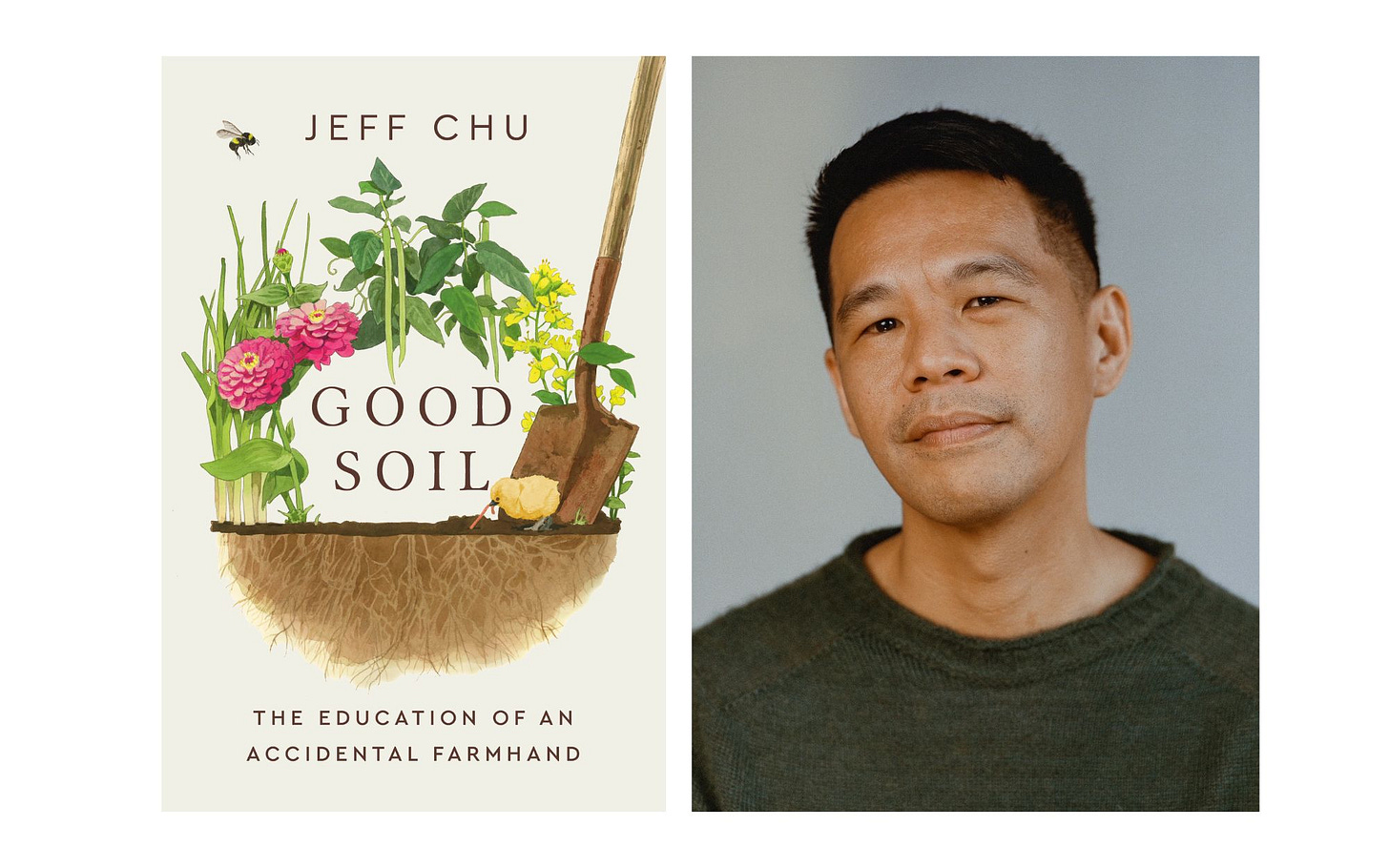

was in his late thirties when he decided to pivot from his position as a magazine writer to theology student and “accidental farmhand.” In his newest book Good Soil: The Education of an Accidental Farmhand, a memoir in essay form, Chu reflects on his years at The Farminary, a 21-acre working farm that connects physical cultivation and land stewardship with a theological education.I’ve followed Chu’s writing for a few years now, drawn to his thoughtful explorations of food, place, identity, and faith. Throughout Good Soil, Chu wrestles with questions of identity, spiritual curiosity, and belonging, returning again and again to the poignant metaphor of good soil. As Chu shared with me, “What's good soil now could be poor soil through a few years of exploitation and misuse. What's poor soil now can become good soil, with enough attention and love.”

In researching the land’s history, tending to the compost pile, harvesting crops, and feeding his friends and loved ones, Chu observed the necessary interdependence of all living things. His words are tender and hope-filled, balms for the weary in search of beauty and flavor and respite.

I was grateful to receive an advanced copy of Good Soil and E-mail responses to a few questions that arose as I read through this beautiful book. I’m excited to share the following conversation with you all!

Sarah Southern: How have food traditions and the act of preserving them (whether through memory, practice, or writing) shaped your sense of self? In what ways do you carry these traditions forward today?

Jeff Chu: Eating is something we all do! In Chinese families, we are not, for better or worse, particularly good at expressing affection verbally, but we're great at making sure everyone is well-fed. It tells you something when the traditional way to greet a friend is not, "How are you?" but, "Have you eaten?"

As I've gotten older, I've realized how much of what I love to eat has been shaped by what I was fed growing up. None of my grandparents is still living, but remembering what my grandmothers fed me—the fried rice that my paternal grandmother made, the silkie chicken that my maternal grandmother cooked—helps me stay connected with them. As I've become a better cook, I've also learned to hold tradition a little more loosely. I've been places and tasted things and experienced aspects of life that they did not, so my husband and I are also creating our own food traditions. Brisket fried rice, for instance, is something that both honors my heritage and incorporates his (he's from Texas, where brisket is sacred).

SS: The narrative of Good Soil seems to culminate at the table with the feast you prepared for your final exam at the Farminary. What is it about a communal table that makes it sacred, and how did that experience shape your understanding of community, faith, and nourishment?

JC: I think it takes attention and intention to make a communal table sacred. In my family, dinner was non-negotiable—there was no option to eat on your own, or any suggestion that one could have something different from what my mom had prepared—and before we ate, we always paused for a prayer of gratitude. In that sense, the communal table became a regular place of shared thanksgiving, a way of acknowledging things that matter beyond our individual selves. And when we went back to Hong Kong to visit family, the communal table was where we gathered, in celebration and joy at life's major moments but also in the midst of fierce fights or significant grief. It was the nexus of our lives, the point where we had no option but to meet.

I suppose that's why it was fitting that my time at the Farminary culminated in that ten-course feast: My time as a farmhand was joyous and challenging, marked by both delight and pain. It seemed right that this should all come together at a shared table, with some of the most important people on that journey. And the dishes I served—those, too, told stories, of my heritage and culture as well as the life I've built with my husband as well as what the bounty of the farm offered. Everything intertwined in that meal, which allowed us to hold all the complexity, all the goodness, all the grief, at once.

SS: In the book, you share your journey of coming out and the challenges of acceptance—within yourself, your family, and evangelical spaces. How did the inclusion of your coming out story shape the way you approached writing this book?

JC: This might not be the most popular way to talk about coming out, but I'm going to say it anyway: Coming out, at least for me and my family, contained a lot of grief. I had to grieve that my relationship with my parents might not ever be what I'd once hoped it could and would be. They had to grieve whatever goals they'd imagined for a son who was supposed to be heterosexual, including the idea of a daughter-in-law who might produce nice little Chinese Christian grandchildren. We had to grieve the ease that we'd lost as well as the perception that we shared certain theological convictions. There were a lot of layers to our grief—and those haven't entirely gone away.

The thing about the farm, though, is that it taught me how loss and grief don't get to have the last word. I wanted to tell a story in which pain, strained relationship, and differing beliefs are very real and inescapable realities—and also, there's something more, something more hopeful, something more promising. That's the little sermon that the compost pile teaches: We name and acknowledge what has died. Then we do what we can, but we also must wait, to enable new life to come.

SS: You write vulnerably about balancing your Chinese heritage, your early experiences with religion, and your later spiritual exploration beyond the faith of your upbringing. How do you balance honoring both your heritage while also embracing the faith convictions or practices you now hold?

JC: I'm not sure "balance" is the right word, because it seems to imply that my heritage and my faith are somehow at odds. The deepening of my faith, which is more expansive than I ever imagined it could be, has made space for me to better honor my heritage. It has allowed me to let go of seeing things as black and white, and either/or. If my faith is really rooted in a belief in a God who is even more gracious and loving than we could imagine, shouldn't it be able to handle complexity and ambiguity? That has been one of the gifts of letting go of the need for certainty and embracing holy curiosity: There is so much goodness to be found in being able to say, "Well, I'm not sure, but maybe..." and "I don't know, but perhaps...."

SS: Your writing blends memoir, journalism, theology, and cultural commentary. How do you approach balancing personal narrative with broader themes in your work?

JC: I enjoy reading memoirs and personal essays, and the ones I love most are the ones where the writer gives just enough particularity and specificity while still leaving white space for the reader to see intersections with their own lives. For instance, when I write about my grandma, and all that she went through, as a survivor of war and as an immigrant, I want to be hospitable in inviting the reader to think about their grandmas. In other words, the personal narrative has to serve a purpose not just for me—because then I should have just kept it all in a journal—but also for the reader. There are also many places in my writing where I go on little digressions—exploring the history of the plum blossom, delving into the Indigenous heritage that marked the land that became the Farminary, introducing some backstory to the zinnia and the killdeer. All of these, too, have to have some point beyond doling out factoids and larding the narrative with information, and one of my goals is to show how we do not exist in isolation but rather in relationship, even across time and space. Obviously those who pick up the book will be the ultimate judges, but I like to think that I've written this with just enough restraint and edited carefully to make it all make sense.

SS: Your book engages deeply with the question of belonging. Throughout Good Soil, you write of wrestling with what it means to belong to yourself, your partner, your family, and your community. How has your understanding of belonging evolved? What role did your experience on the farm play, and what does belonging look like for you now?

JC: I wonder sometimes whether the consumer-centric, consumption-obsessed culture of the United States has unwittingly programmed us to think that belonging is a thing we must be offered—a product, almost. We want it to be convenient and delivered on demand. That's not how belonging works. That's not how community works. It takes faithful and sacred labor. There will be extremely challenging moments when you're compelled to ask hard questions about how you, and your actions, and your feelings, and your way of moving through the world affect others, and their actions, and their feelings, and their way of moving through the world. On the farm, I learned, too, that there are some things I can control and many I cannot—and discerning which is which might be the toughest part of being human. We will all make mistakes! Can we summon sufficient grace, for ourselves as well as for others, to handle those?

On my better days, belonging is more something that I create for others and less something that I demand from others. It might mean cooking a meal for my husband that I know will bring him back to a happy place or a text message reminding my best friend how much I love him. It might be offering a blessing to my newsletter readers, because I suspect that this moment in time is a particularly challenging one. It might mean scribbling a postcard to a friend, because it's so rare to get old-fashioned mail. It might mean setting aside my own preoccupations long enough to send up a few prayers on behalf of some acquaintances. It might mean taking some potatoes that we've harvested from our garden to a neighbor. There are so many ways to create belonging.

SS: Since graduating, have you continued farming or gardening? How does the “good soil” metaphor continue to show up in your daily life, both in terms of your work and personal growth?

JC: My newsletter is called "Notes of a Make-Believe Farmer" because I'm not a real farmer—nobody depends on what I grow for their sustenance—and also because the primary thing I've cultivated in the garden is hope—the growing things have made me believe in the promise of things beyond myself. We have a couple of raised beds and a little space in our yard. A couple of years ago, I planted some blueberry bushes as well as some asparagus; the raspberries somehow came up on their own. Garlic is growing there right now. In May, the community garden will open; I've tended roughly the same 12x50 space for the past several years, and it's been wonderful not only to plant what we like to eat (tomatoes, peppers, beans, potatoes, greens) but also to harvest what I didn't grow (someone who had that space before me put in gladioli, and they just keep coming back on their own, which is its own particular testimony to grace).

The "good soil" metaphor is such an interesting one. It comes in part from Jesus's parable of the sower, in which we are told of the "good soil" that produces a hundredfold, as opposed to the rocky soil or the thorn-choked soil. Growing up as a Baptist kid, I always read that passage as a threat—you have to be the good soil, or else.... Gardening has helped to teach me that "good soil" is not a permanent end state. Soil is dynamic. It needs amending, and it needs rest. What's good soil now could be poor soil through a few years of exploitation and misuse. What's poor soil now can become good soil, with enough attention and love. The metaphor and the parable, as I understand them now, are less a warning about impending judgment than they are a kind word about potential and possibility. The parable is, after all, supposed to bring good news.

Good Soil: The Education of an Accidental Farmhand releases today and available for purchase here.

Loved this interview, and I'm looking forward to reading his book!